Attraction

Recreation

Ichan-kala museums display unique specimens of carved wood, chasing, jewellery, armament and glazed ceramics dating to the 9th-20th centuries. Quite special are marble slabs and column bases bearing inscriptions and designs, woven items and carpets, traditional costumes, leather items, etc.

In the 8th century, the Arab conquest of Central Asia brings Islamic religion to the land between two rivers. This was the time of fundamental changes in the culture and art of Khorezm. The new ideology influences the appearance and structure of the cities, new religious and administrative installations are being built, such as mosques, madrasahs, mausoleums, caravanserais… Starting from 9th-10th centuries, architecture and crafts come to the forefront, while monumental types of representational art, such as murals and sculpture, disappear; items related to former cults and religious beliefs, namely ossuaries, go away from sacral use. Art content and themes also change: figurative images disappear, replaced by ornamentally-plane style of vegetable and geometric designs. Ornament becomes key in the decoration of numerous articles of Khorezmian artistic craft, among which glazed ceramics becomes most widespread. Ornament in the form of glazed tiles, plaster and wood carving infiltrates the decor of new architectural structures. Starting from 11th-12th centuries the use of baked brick, carved terracotta and glazed tiles as construction materials and carved wood in decoration had set the foundation for new aesthetics in Khorezmian architecture.

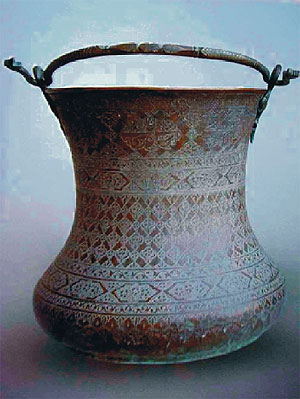

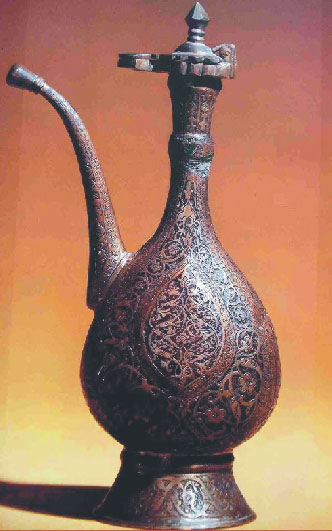

The 11th and 12th centuries saw processes in applied arts that were typical to the entire Central Asian territory between the two rivers; these processes were linked with the strengthening of ornamental origin. Items made of glazed ceramics and glass become widespread. Unfortunately, no metal items wrought in Khorezm before the 18th-19th centuries were found; however, in some later articles (kumgans) one can clearly sense the connection with the shapes of the 6th century A.D. Sasanid items. To manufacture glazed ceramics, potash- and lead-based glaze was used. Despite the use of vegetable, geometric and epigraphic themes, the decor of Khorezmian articles, unlike, say, Samanid ceramics of Maverannahr (Afrasiab, Chach, Fergana, Chaganian, etc.) appear to be less saturated with patterns, with basically no zoomorphic motifs, and calligraphic inscriptions are few and insignificant.

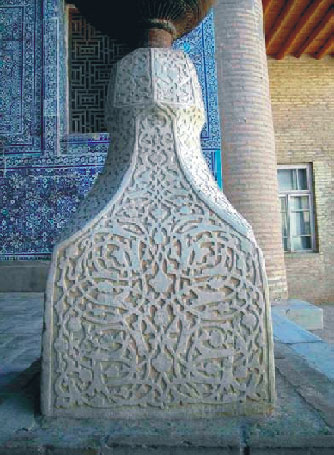

On the verge of the 12th and 13th centuries the power of Khorezm-shahs, who retained the title of Great, spread over an area from Caucasus to Indian border. A great empire was created, and Khorezm experienced an extraordinary economic rise. Irrigation system is expanded and improved, irrigated area is growing, and trade with Maverannahr, Khorasan and Dashti-Kipchak is intensified. Arabic traveller Yakut wrote about Khorezm of that time: “I journeyed through it in 618 (1219) and never did I see a land more flourishing… Most of the settlements in Khorezm are towns with market-places, life goods and shops. Seldom can one find a settlement with no market-place” (1, p. 419). Science, culture and arts develop rapidly; ceremonial secular and religious buildings are erected and richly decorated with carved plaster, painting and glazed tiles. Architectural elements such as doors and columns are adorned with splendid carving. New shapes appear in non-glazed ceramics, and in glazed ceramics they start improving the process of glaze-making; crockery is now made of kashin-semi-faience.

Further development of the Great Khorezm-shahs’ empire was put to an end by the invasion of Genghis Khan’s army that delivered a mortal blow to the economy of a thriving land, bringing it to collapse and decay. Yet already by mid 13th century the economy of Khorezm began to recover. During that period the development of the Golden Horde ceramics was strongly influenced by a more advanced pottery school of Khorezm (2, p. 301). In the 14th century Urgench again becomes the capital city, which, according to the contemporaries, boasted “…beautiful bazaars, wide streets, and numerous buildings”. Along with mosques and madrasahs they also mention palaces, hospitals, market-places and residential houses. Here is the description of interior decoration of a palace of a Golden Horde governor of Khorezm, Kutlug Temur, who eventually proclaimed the independence of Khorezm: “We entered his house, then proceeded to the minor reception room with decorated wooden dome, walls adorned with multicolour fabrics, and the ceiling – with gilded silk” (3, p. 104). The interior decoration of the city elite houses was also a colourful picture. The guest room (mihman-hana) of an Urgench justice Abul-Havsa Omar had “splendid carpets, walls were covered with textiles and had lots of niches – in each of them stood gilded silver vessels and vessels from Iraq…” Further Ibn Battuta added, “…that is the custom of the people of this country – to decorate their homes”.

In the 14th century, glazed ceramics still held leading position among artistic crafts. Its shapes become more diverse, the quality of crockery is improved, and its finest varieties are now made of kashin clay. Ceramics of that period features the diversity of artistic and technological methods, such as under-glaze and over-glaze painting, engraving, stamping, relief, etc. Primary decoration motif is vegetable, but zoomorphic designs could also be found, reflecting connections with China and Iran. By the 14th-15th centuries “cobalt”-style items featuring blue painting on white background in imitation of Chinese porcelain became very popular in Khorezm. Glazed ceramics was even more widely and diversely used in architectural decor: there appeared deep-light-blue and white tiling that set the foundation for new Central Asian style. New large buildings are erected not only in Urgench, but also in Khiva, Mizdakkhan and Narinjan.

In the end of the 14th century Khorezm became part of Amir Temur’s empire. In the 15th century skilled Khorezmian architects and builders brought to Samarqand and Bukhara took part in the creation of unique monuments of Central Asian architecture such as Jahangir’s mausoleum (Hazrat Imam), Ak-Sarai palace in Shahrisabz, Chashma Ayub in Bukhara and others. In Khorezm itself urban development was suspended, economy fell into decay due to the reduction of irrigated area and weakening of trade activity in the region. The level of the 17th-18th century craftsmanship also goes down; the mastery of shaping and painting glazed ceramics deteriorated. According to texts, that was the time of jewellers, wood- and stone-carvers and engravers; glass manufacturing still existed; weavers produced silk and cotton fabrics, yet there were no patterns anymore: fabrics were painted in one colour or in multicolour stripes.

Up until the end of the 18th century construction activity was weak in Khorezm; in the 17th-18th centuries in Khiva they built only few monuments worth mentioning. Only in early 19th century active development began in Khiva. Among the city’s monumental structures the prevailing buildings are mosques, mausoleums, minarets and madrasahs, and the latter are more numerous. One characteristic feature of Ichan-kala buildings is the extensive use in interior decoration of contrasted blue-white glazed tiles and numerous wooden columns, gates and smaller doors with expressive and original ornamentation.

Applied arts of the 18th and early 20th centuries are represented by different kinds of art, the specimens of which are kept in museum collections in Uzbekistan. One specific branch of artistic craft was the art of the nakkosh – the artists who created ornamental compositions for all kinds of art. History has preserved the names of lead masters among the magicians of design who lived in the first half of the 19th century: usto Mirza, usto Matpano and a well-known virtuoso Abdullo-Jin. The most remarkable pieces of applied art were created in a synthesis with architecture: these are carved wooded columns, doors and gates – wonderful specimens found in great numbers in Ichan-kala monuments. Many household items were also made of wood: small carved tables, book-holders (lavha), cases for porcelain vessels (chinnikap), chests, cabinets and other items. The art of making compositions of deep-light-blue and white tiles reaches its heyday. The walls of madrasahs, mosques and palaces are decorated with the infinite splendour of these patterns. At times one could get an impression that they lost their constructive qualities and turned into unique masterpieces of design-making. Stone-made items were important for the decoration of building interiors: column bases with ornamental inscriptions and slabs with carved inscriptions.

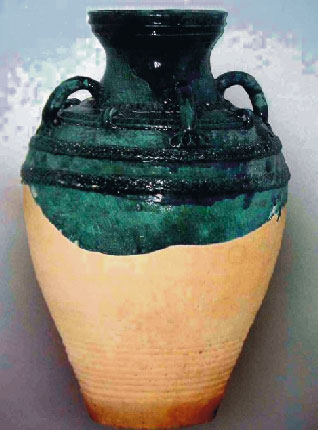

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise in the development of glazed ceramics. The mastery of ceramic-makers manifests itself in manufacturing both architectural specimens and household items: the most popular item of that period was a platter, badiya, with vertical sides – the shape that was characteristic only of Khorezm. Lead colouristic feature of Khorezmian ceramics becomes green colour of different shades, with inclusion of blue-white details, due to widespread use of ishkor glazing. There emerge key centres of Khorezmian glazed ceramics, which preserved their importance also in the second half of the 20th century: Khiva (Hanka), Madyr, Kattabag, Bagat and others. Ceramics masters, namely usto Yusup, usto Iskandar Kalantarov, usto Veis and others earned fame. Item decoration starts featuring objects such as knives, vessels, musical instruments, etc. In the 20th century the most renowned ceramics master was Raimberdi Matchanov from Madyr settlement near Khiva, who created wonderful items, both in terms of technology and ornamental grace.

The 18th and 19th centuries were the time when Khorezmian chasing reached its fullest flower; it is the most popular kind of applied art after wood-carving, glazed ceramics and jewellery-making. In the second half of the 19th century in Khorezm there were about forty copper-smiths united in an industry corporation, manufacturing various items: jugs, trays, vessels for water and boiling, pails, wash-basins, etc. Khorezmian chasing style is typified by graceful outlines, laconic shapes and graceful ornamentation. Another sub-section of artistic metalworking is armour- and jewellery-making, which became highly developed in the 19th century. Jewellers used the richest range of precious metals, gemstones and working techniques, creating unique women’s jewellery, arms and horse harness. They widely employed techniques such as filigree, incrustation, engraving, chasing, moulding, etc. Very colourful and expressive are takya duzi jewellery – cap decoration that was fastened to it (back-of-the-head decoration uk-yoi, bow and arrow), yarim-tirnok temple-and-ear pendulum, manglai-tuzi or osma-tuzi forehead decoration in the form of shaped plates adorned with gemstones.

Khorezm was also famous for carpet-weaving – mostly the engagement of nomadic Turkmen or Karakalpak tribes; Khorezmians also kept carpet-making looms in their households, and women used them to manufacture fleece carpets and other household items. During that time Khorezm produced different silk, semi-silk and cotton fabrics. Also common was the art of Khorezmian printed cloth – two-colour and polychrome. The main manufacturing centres were Hanka, Chitgaron, and Chimbai. In Khiva there was a special district of printed cloth manufacturers. Wood-carvers produced special kalyb – matrices to apply a pattern on a cloth. Printed cloth was produced in sheets and was used to make clothes, tablecloths and other items.

The art of Khorezmian peoples has always evolved in an active interaction with traditions of contiguous regions, yet they developed their own consistent and peculiar artistic language and definite forms. To present day, the original culture of Khorezm has preserved its traditions, which, going through an artistic renewal, enrich modern life and give the world their inspired and remarkable specimens. Ichan-kala is one of them; not only is it a keeper of a many centuries old heritage of Khorezmian culture, but also a source of a living and evolving tradition of folk art.

Today in the shade of cozy courtyards the flocks of teenage boys, guided by their mentor, enthusiastically work on various wood articles, decorating them with traditional Khiva design, and Khiva girls work to restore traditional Khiva textiles, such as printed cloth, fabrics and carpets. Traditional culture of Khorezm is breathing again in a new life of independent Uzbekistan.

Literature

1. Цит. по кн.: “Материалы по истории туркмен и Туркмении”. Т.1. М.-Л., 1939.

2. Вактурская Н. Н. Классификация средневековой керамики Хорезма IX-XVII вв. Керамика Хорезма / Под ред. С. П. Толстова и М. Г. Воробьевой // Труды Хорезмской археологической экспедиции. Т. 4. М., 1959.

3. История Хорезма с древнейших времен до наших дней. Ташкент, 1976.

Akbar Khakimov